| ||

|

|

Jackson, (Bottileas) - Amador County, California | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jackson - that city which gold, girls, gambling, gastronomic delights and government has kept lively for over 150 years - was born in the gold rush. Gold seekers passed through the fording place where two forks of a small foothill creek met, headed for the rich Mokelumne River sand bars. Others, dead broke or enriched, returned via the place to Stockton or Sacramento. Who stayed? Probably no one in '48, but a laterday obituary said that one Louis Tellier, a 28-year old Frenchman via St. Louis and the Sandwich Islands, set up his trading tent by the forks in January, 1849. Had there been a poet on call he might have dubbed the place Springford or Fordsprings. One story notes that the spring became littered with discarded bottles, so Spanish for 'place of bottles" or Bottileas it became-even though there's no such word in Spanish. It wasn't Bottileas for long. Sometime before the fall of '49, Bottileas became "Jackson's Creek." Maybe it was named after New York native Alden Appolas Moore Jackson or Andrew Jackson. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When the Placers ran out, probably only Jackson's Creek's spring and location at the ford kept it alive. When gold quartz was discovered in the county in 1851, the only major quartz mine south of Sutter Creek was the Oneida, a good two miles away. Nonetheless, the camp became that day's regional shopping center, and miners flocked to the place. In 1851, at least three events ensured the camp's permanency: it got a post office, stage coach service and the spoils of the Calaveras County seat. By 1852, politicians in Jackson tried to create a new county. When secession attempts failed in '52 and '53, Jackson incorporated. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

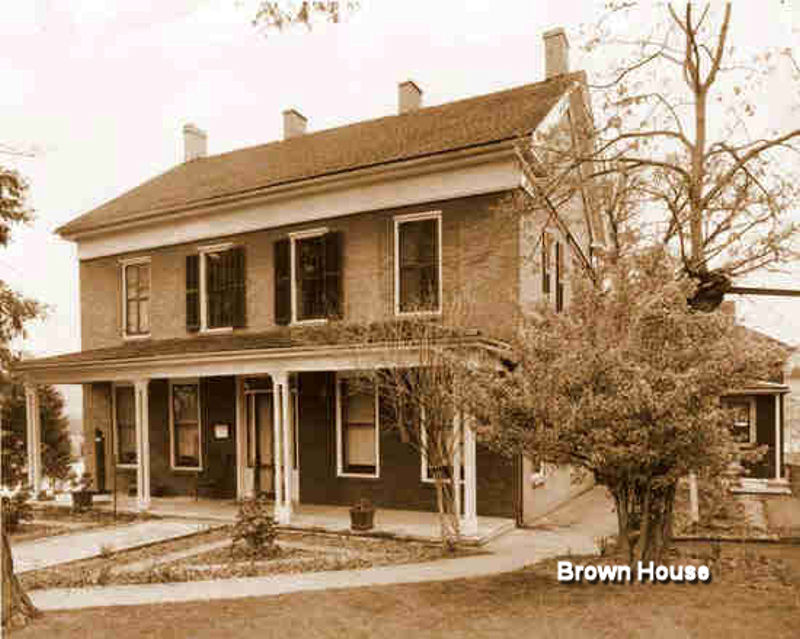

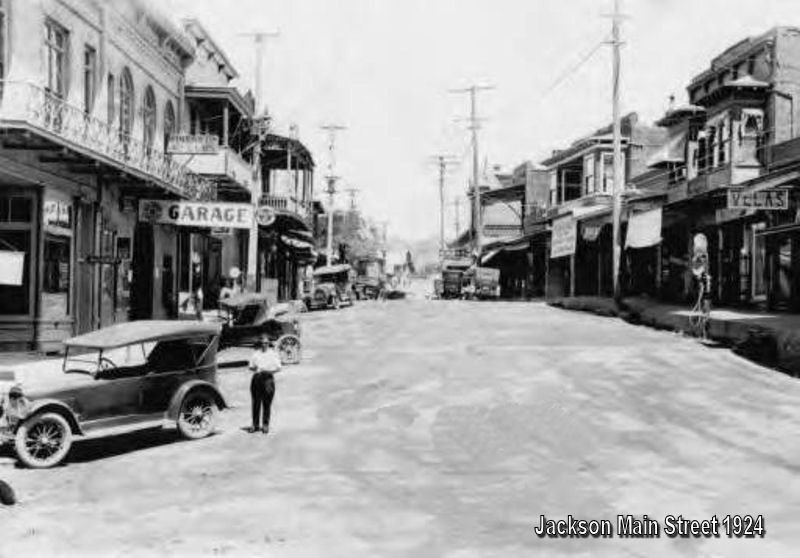

When Amador was organized as a new county in 1854, Jackson eked out a win over Volcano to become the new county's county seat. Fixary & Co., a French firm which started in "une certaine tente" in 1851, erected the first brick structure in the summer of 1854. One account that summer said Jackson "has over 1 00 frames, some two-story." Later that year the thickwalled, two-story brick building (today's Masonic Building) was constructed at the corner of Broadway and Water. It wasn't until 1855 that fire destroyed a major portion of the town. That blaze was a mere introduction to the town wide conflagration that destroyed most of Jackson on August 23, 1862. If you look behind modern window treatments and various facades in downtown Jackson today, you'll discover buildings that arose following the 1862 great fire. While Jackson had quartz mines from the 1850s, none of them - not even the famous Kennedy or Argonaut on its outskirts - were continually profitable until late in the 19th century. The Kennedy didn't hit real, sustained pay chutes until 1885, and the Argonaut didn't for another decade or more. But once started, their depths disgorged pay ore almost continuously until World War II shut them down. At the 19th century's turn, Jackson had about 3,000 residents, in city and environs, with three churches, three newspapers, four hotels, five boarding houses, two candy factories, cigar and macaroni factories, eight physicians and two dentists. Jackson, in 1905, incorporated as a city. Its first mayor was V.S. Garbarini, the mechanical genius. Its other first trustees were George W. Brown, W.E. Kent, William Tam and the Dispatch publisher, William Penry. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

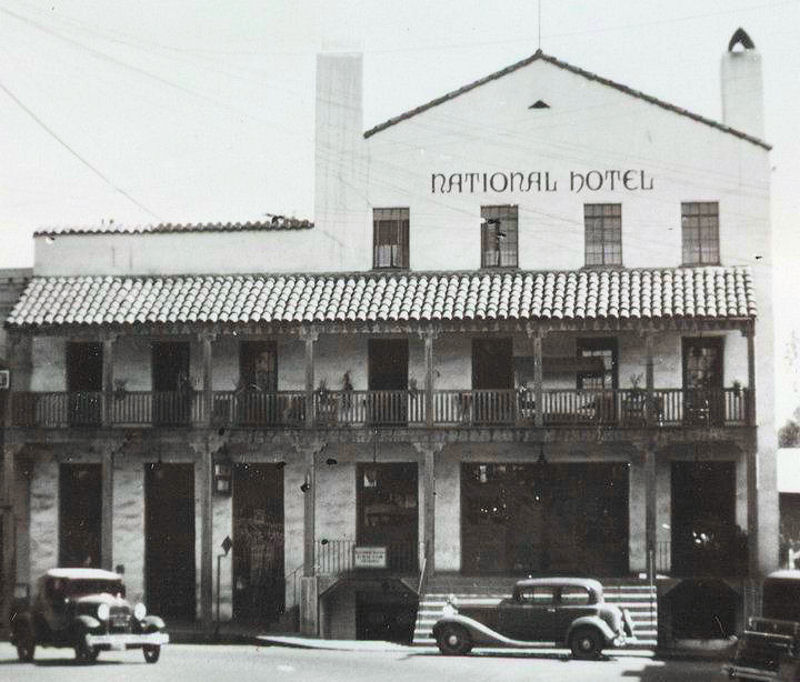

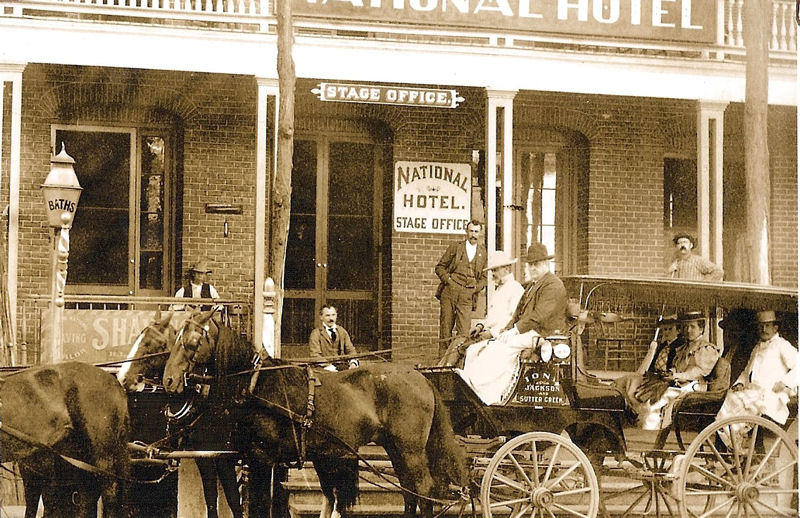

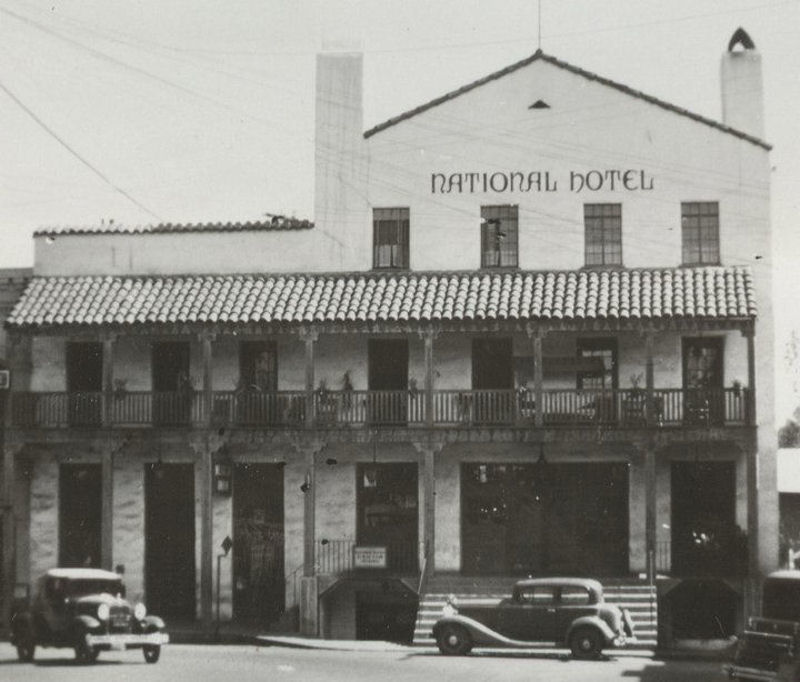

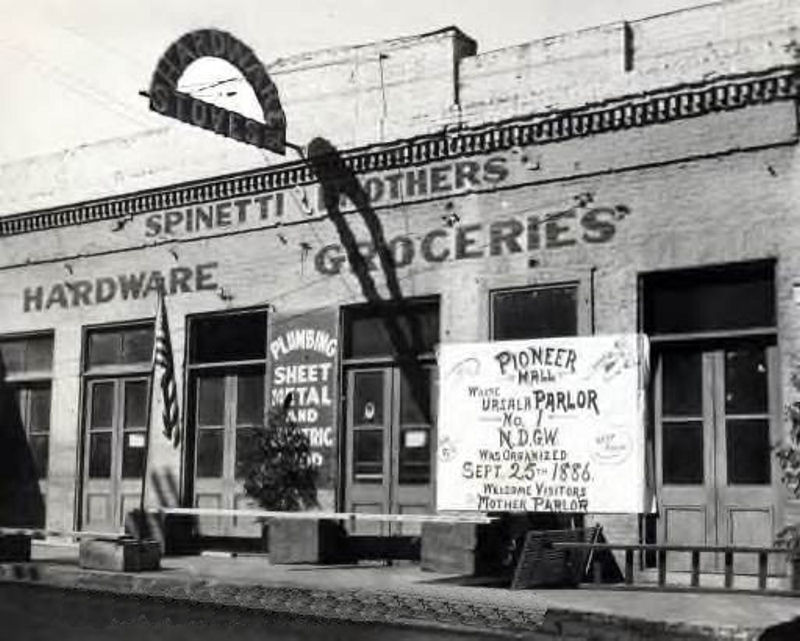

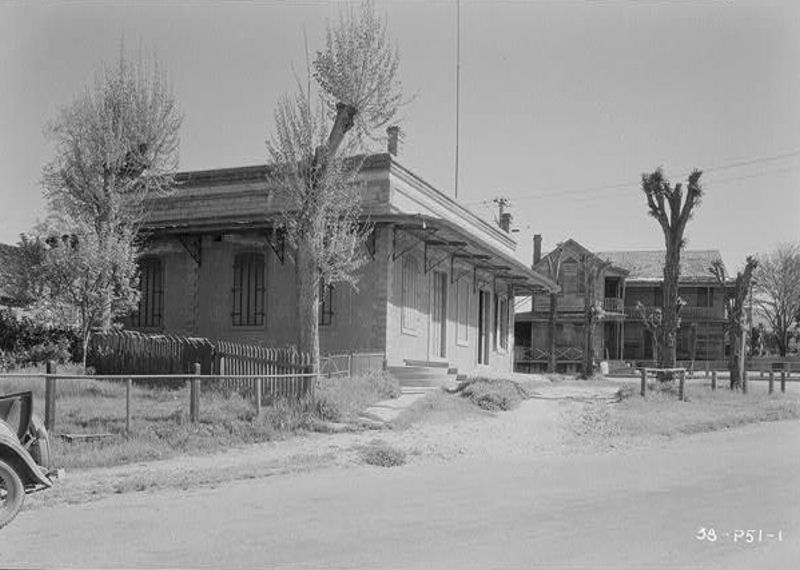

Old Jackson Photos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Information, photographs courtesy of the Amador County Archives, The Historical Marker Database, The Chronicling America Database, and Larry Cenotto, Amador County's Historian CONTACT US

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||