|

|

Upper Rancheria, Amador County Ghost Town | ||

|

Hale Road, itself, is an experience! Like other back roads in Amador, the road named after the Walter Hale family in the area - probably follows its original 1850s alignment and seems not a whit wider! From Shake ridge it drops hundreds offeet to a vale near Upper Rancheria, and then descends several hundred more into Dry Creek's south fork where Samuel Loree's pioneer tool bridge spanned. A road two miles down Shake, Stone Jug road. The 1866 county map shows both as comparable roads. Unpaved Stone Jug leaves Shake, heads directly north, and arrives at Upper Rancheria in about 2.5 miles. A private gate stops you, as it is now private property. |

|

|

|

Probably its first miners named the creek after its Indian rancheria, and named the first camp along its banks, Rancheria, too. Later, when another camp sprouted next to the creek upstream, it was named Upper Rancheria, to differentiate it. Most miners though called the lower camp "Ranchoree." In fact, that was the early name for what became the Bunker Hill mine which lay near the creek. If Amador county has what map makers might call a terra incognito, that is, a block of land that is relatively uninhabited, undeveloped, unknown, un-urbanized, Upper Rancheria would be part of it. Look at any county map, as I did after a recent field trip. Note the expanse between Shake ridge and the Fiddletown-Silver Lake road, and from highway 49 upstream for 10 miles. A swath of land three to five miles wide, cut by numerous creeks and middling forks of creeks, through flats and relatively deep canyons. A rugged section, mostly untouched except by miners and ranchers. Maybe many hike, or hunt there. |

||

|

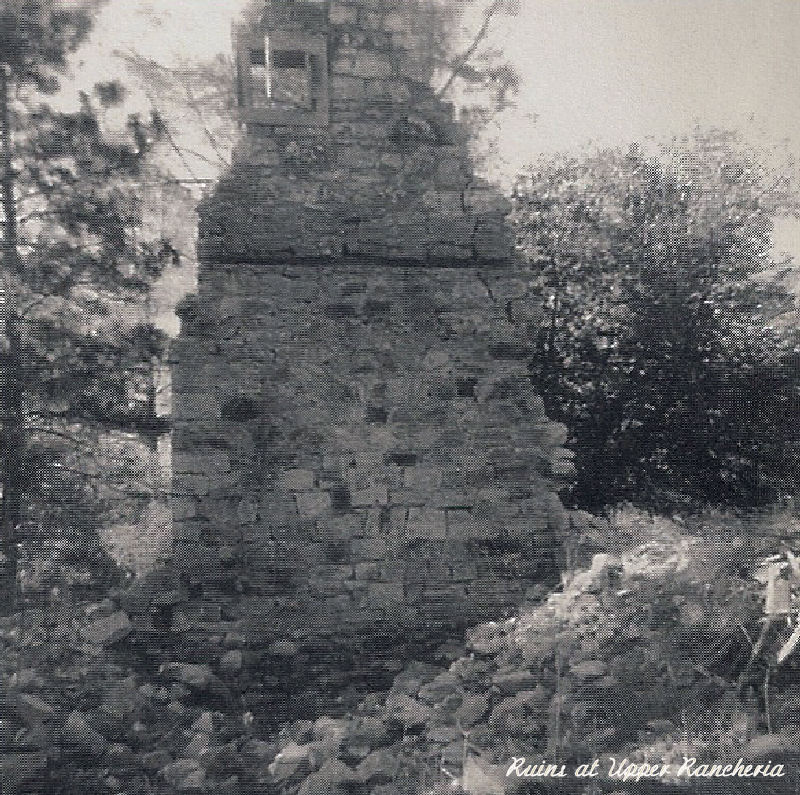

Cowmen in the small years of the 20th Century in search of stray steers reported riding into and down a long street lined by great stone buildings, some of them of two and one of three stories, their burnt-out shells throwing their skeleton forms against the skyline. To this day that entire country is completely uninhabited. An examination of the town site will show that is was built around the foot of an almost perfectly circular mountain, flat at the top, the buildings forming half of the hub of a wheel. |

|

|

This scene of ruin and desolation discovered by artists perhaps thirty years ago was the source of canvases of great beauty that were exhibited on the West Coast and perhaps were viewed in an even wider circle. If one wishes to bring utter destruction, desecration, and befoulrnent upon a ghost town, all that is necessary is to let its site be widely known. And by an inverse reaction these paintings accomplished just that. One by one, using the advanced techniques of modem engineering, these structures were numbered part by part, disassembled, transported, and re-erected at points far and wide in exactly the same way that William Randolph Hearst caused monasteries and churches in Spain and Italy to be moved to San Simeon. The very last remaining building was removed stone by stone and re-erected as the Stone Jug in Volcano in the 1950s. At the site, if one does not take into account cellars and basements, not one stone remains atop another. At nightfall, if a word from the present inhabitants is desired, one must listen to the wail of the coyote from the thickets of madrone and the whoo-whoo of the moping owl on the bluff overhead. | ||

| ||

|

Information, photographs courtesy of the Amador County Archives, The Historical Marker Database, The Chronicling America Database, and Larry Cenotto, Amador County's Historian CONTACT US

|

||